"If you’re fair and sweet, don’t wear it."

‘If you’re fair and sweet, don’t wear it,’ declared Christian Dior after the 1947 debut of his ‘New Look’ collection, the first by any designer to feature leopard print on the runway.

Throughout the twentieth century, leopard has stood as a polarising print whose meanings have been shaped by those who wear it and those who do not. Leopard print can be high fashion and expensive, it can be trashy and tacky, it can make one stand out and it has been considered a neutral. Famous characters, both fictional and real, have come to be defined by the print: Edie Sedgwick, Jackie Kennedy, Joan Collins, Pat Butcher, Bet Lynch, Kate Moss Naomi Campbell, Debbie Harry, Divine and Scary Spice. All are famous for their love of leopard print, yet each employ it in diverse ways and invoke different reactions indicative of the relationship between fashion and identity.

Fashion is an unspoken visual language that expresses personality and communicates to the outside world how we see ourselves and how we want to be seen. It is a central way identity is performed and read by others and therefore inherently linked to ideas surrounding gender, class, race, age, and sexuality. Fashion is particularly prevalent to youth culture and a key component of young people’s identity formation as they experiment with different cuts, fabrics and patterns that are transformed into symbolic statements about who they are. Ever since humans began wearing garments ‘they began assigning meaning to every aspect of them,’ and leopard print is no different. Jo Weldon has defined the print as ‘a pattern that helps animals blend in and humans stand out.’ It is a contested and contradictory print worn by Mods, Punks, Rockers and Drag artists and by women young and old from every social background. Its increasing availability throughout the Twentieth Century has seen it evolve from expensive furs worn exclusively by the wealthy in the 1920s, to a subversive symbol of rebellion and rejection of societal norms employed by different youth subcultures.

My own love affair with leopard print began when I was around 17 years old and I now have over twenty items of leopard print clothing in my wardrobe. Skirts, t-shirts, jumpers, coats, and shoes: if it’s got leopard print on it, I want it. My affection for the print stands at odds with the rest of my wardrobe, a neutral palette of muted colours. Generally, I don’t like prints. So, what is it about leopard print?

When asking people why they do or do not wear it and what personality traits they associate with people that do, the most common answer was ‘it just doesn’t suit my personal style.’ Opinions on those that do included: loud, classy, confident, fierce, sassy, independent and strong. However, the dangers of wearing ‘bad’ leopard print were also stressed, with a warning that the print can also look ‘tacky’ and ‘cheap.’ While writing this piece, I began to explore what it really is about the print I love so much and give serious thought to how it makes me feel. I love leopard print for the versatility of its warm brown tones that fit my affinity for more neutral colours. Wearing the print makes me feel more confident, whatever the situation, which may come from its historically subversive nature. I have become known for wearing leopard print and consider it part of my identity.

Whatever your opinion of leopard print, it evokes a strong reaction.

The most examined aspect of the relationship between fashion and identity is that of gender. Joanna Entwistle has stressed fashion’s historical role in the emergence of the gender regime to sharply distinguish male and female through styles of ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ dress. Readings of leopard print are highly gendered, with its feline nature making it a print most often, though not solely, worn by women. However, age also has ramifications for the way leopard print is read. The 1940s and 1950s saw the evolution of the print toward an association with eroticism as it became a staple on women’s lingerie and swimwear, epitomised in the rise of pin-ups and bombshells such as Marylin Monroe and Brigitte Bardot. This gendered sexual image was one defined by youthfulness. A quick internet search will reveal an understanding of a ‘wrong’ and a ‘right’ way to wear the controversial print and this is inherently connected to age. Articles ask, ‘can you dress in leopard print and not look like a cougar?’ and give advice on ‘how to wear leopard print at any age.’ Julia Twigg recognises the often-uncomfortable relationship that exists between fashion and age, asserting that fashion ‘remains preoccupied with the youthful and transgressive’. As one of the key structuring principles in society, age intersects with other identities, especially gender and social class ,in significant ways in the field of fashion.

Older women often do not see themselves in the clothing designed for them due to the restriction of their cultural expression in a ‘hierarchically arranged concept of age’ which positions them on the periphery of fashion culture. This is seen in both the cut and shape of clothing for older women, as well as the prints (or lack thereof) and material used. Leopard print is loud and bold, whereas older women are often provided with ‘darker, duller colours; looser, longer cuts’ and ‘more covered-up, self-effacing styles.’ Simon Wheatley’s image of ‘woman in leopard fur coat,’ however, demonstrates that older women continue to engage with fashion as a form of self-expression and communication of identity. Pops of leopard print alongside a statement bag and pink nails add colour and a sense of personality to her otherwise dark and dull coat. Recognition of older women’s sustained consumption of fashion is leading to the expansion of the ‘grey market’ on the UK high street.

As a print designed to make ‘humans stand out,’ leopard print stands at odds with society’s understanding of the peripheral social location of the aging woman. Negative depictions of women in leopard print deemed ‘too old’ is particularly tied to the image of the cougar. In the 1960s and early 70s films such as The Graduate, introduced us to, Mrs Robinson characters, older, predatory women who shamelessly seeks out younger men for sexual relationships, and wears leopard print while doing so. ‘Cougars,’ have been negatively defined as financially independent women between 35-55 years old, who are desperate to maintain the appearance of youth. The understanding of leopard print, and fashion more generally, as a young person’s game, compounds the narrative of desperation projected on to the older woman wearing the print. While the young woman in leopard print is sexy, attractive, easy prey, the older woman is desperately predatory.

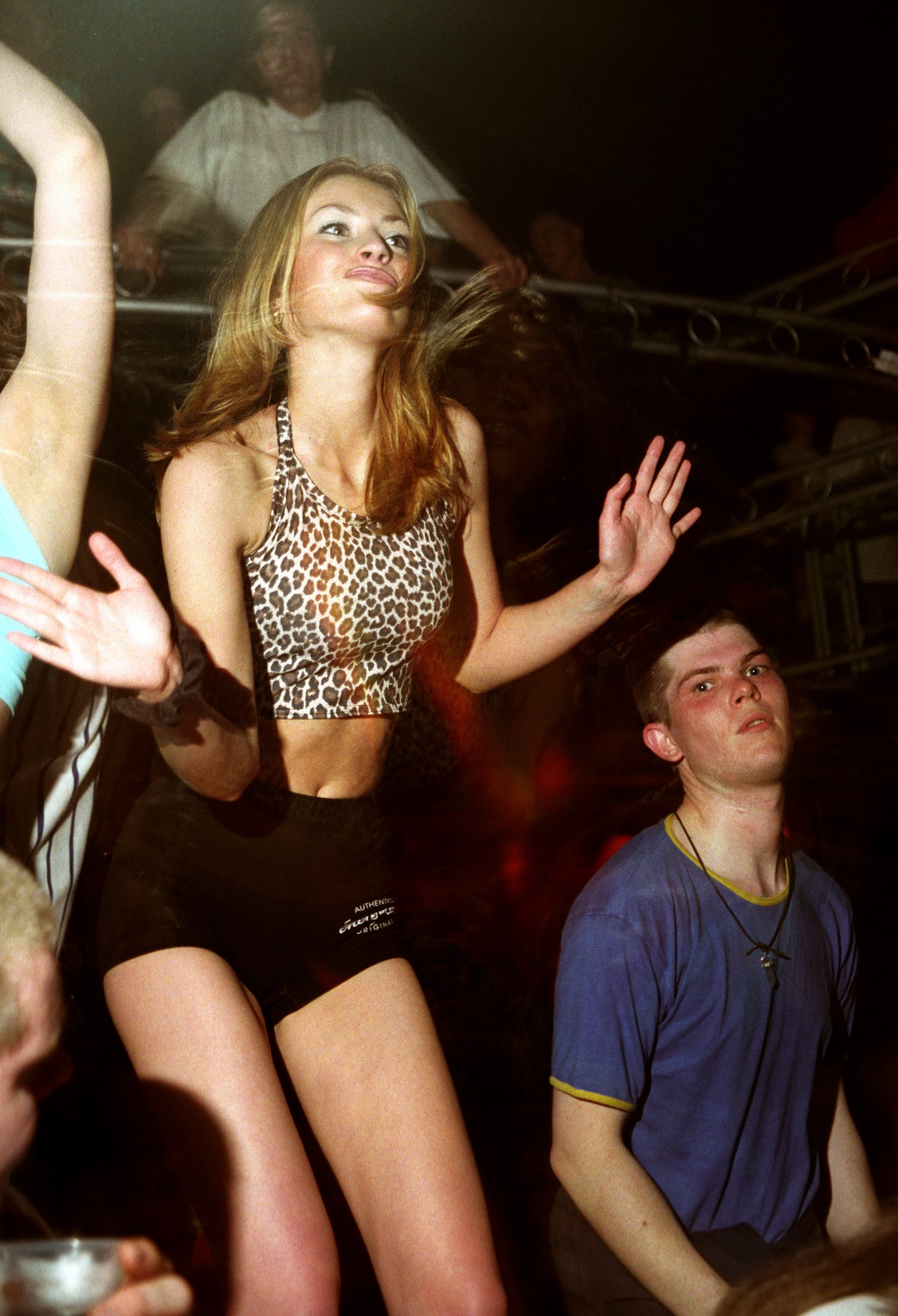

The relationship between leopard print and gendered sexuality continued throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first century. While women have worn it to feel bold and confident, they have often been sexualised, deemed morally loose and assumed sexually available by a more conservative mainstream society. The caption given to Danny Joint’s 2004 image of a young woman in a nightclub signifies the hyper-sexuality inscribed onto the young female body in leopard print. It makes specific reference to the ‘leopard skin outfit’ when describing its wearer as ‘a sexy girl’ and drawing attention to her cleavage. The image itself is one that plays on notions of sexual availability as the woman looks directly into the camera, meeting the gaze of the viewer and seeming to address them directly.

The physical location of the image identified through labelling of the young woman as a ‘club dancer’ further assigns meaning. Nightclubs cultivated specifically for youth provide spaces for experimentation in the search for identity that includes subversive behaviours of the overtly sexual. A sub-culture itself, beginning with the 1980s rave scene, club culture has become increasingly mainstream and a rite of passage that has nonetheless retained its association with the hedonistic consumption of alcohol, drugs, and sex. This understanding of nightclub spaces is extended to readings of club fashion, especially among young women, who is donning of smaller and tighter clothing are often considered by men a sign of their openness to sexual advances. The assumption of the sexual availability of women is a gendered reading projected on to the female body that is not always representative of the message that women are trying to convey. Despite outward readings of the young female body in leopard print as overtly sexual, women have sustained agency in wearing the print for their own motivations, whether that be attracting a romantic partner, for their own self-confidence, or both.

The association of leopard print with female sexuality exists in the cyclical nature of its gendered coding. As the 1940s and 50s cultivated the sexual image of leopard print in pin ups, those who relied on their sexuality to make a living began wearing the print. When women employed in sex work began using the print, in the eyes of mainstream society, the relationship between leopard print and sexual availability was solidified.

Contrastingly, at the same time as leopard print became infused with increasingly sexual meanings for both young and older women, it was also given an air of respectability in 1961 when Jackie Kennedy, already a fashion icon, stepped out in her famous leopard fur coat. Jackie Kennedy had cultivated the image of the perfect respectable housewife and first lady. Her use of leopard print demonstrates the contradictory meanings assigned to the print as it was worn by different people. Not only were meanings of the print informed by the gender and age of the wearer, but also by their class. The significance of class in fashion has been overlooked, however it plays a key role in evaluations, judgements, opinions, and practices of fashion, especially in the UK where class remains a national preoccupation and given the strong association between class and taste. The phenomenon initiated by Jackie Kennedy made leopard print fur, and increasingly faux fur as the 1960s went on, respectable. Wearing a fur coat was a sign of wealth, luxury, and social status. In contrast to the flamboyance, sensuality and aggressiveness of the print worn by younger and older women of lower classes.

"leopard print has been employed by working-class youth cultures in complex ways, defying its singular definition. While some leopard print is given overtly sexual meaning, it has also been employed as a symbol of rebellious respectability."

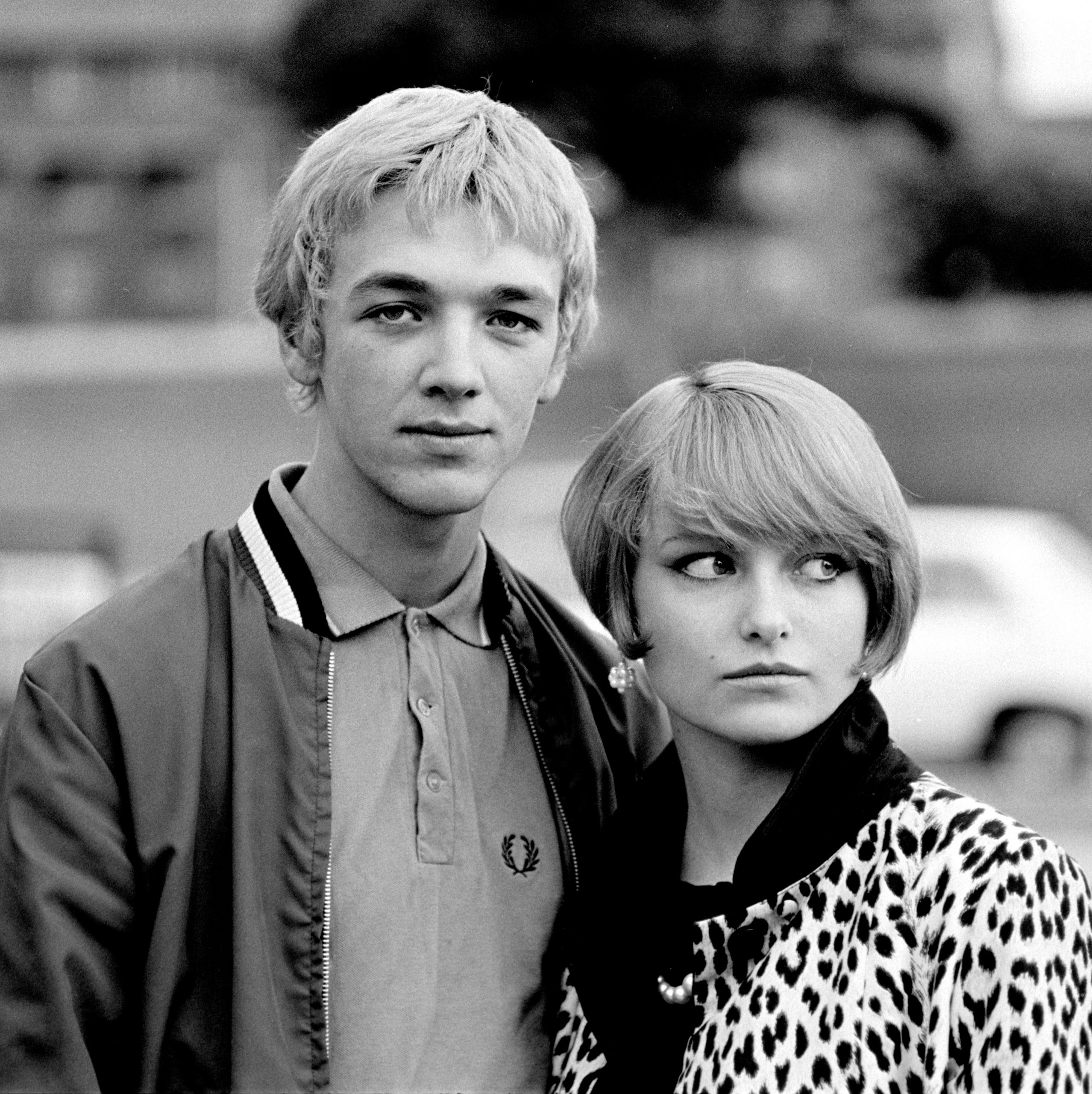

However, with the democratization of fashion and the endeavour to emulate fashion trends of the wealthy, women of the working classes were able to purchase their own, more affordable versions. George Plemper’s ‘Portrait of a young Mod couple’ from 1981 demonstrates this phenomenon. Christine Feldman-Barrett suggests that Mod subculture emerged in London during the early 1960s among working-class youth who sought to rebel against the post-war austerity of their parent’s generation [read full article here]. The woman’s leopard print coat, strikingly like Jackie Kennedy’s, paired with quintessential Mod chin length bob, a ‘pearl’ necklace and kitten heels, creates a clean, neat, and chic silhouette that stands in juxtaposition to her council flat surroundings. Pempler’s image illustrates how leopard print has been employed by working-class youth cultures in complex ways, defying its singular definition. While some leopard print is given overtly sexual meaning, it has also been employed as a symbol of rebellious respectability.

The working-class adoption of styles previously considered exclusive to the wealthy and socially elite has not, however, led to a decline in the relationship between class and fashion as upper classes have sought other ways to distinguish themselves from the ‘bad taste’ associated with the working class. This led to further designations of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ leopard print based on silhouettes, fabric, brand labels and type of leopard spot. Despite historical association of leopard print with wealth, power and status and attempts to maintain its exclusivity, Molly Macindoe’s 2010 image of a woman wearing a blue bomber jacket with leopard print sleeves demonstrates how it continues to be enjoyed by people from all social classes, whether it is considered ‘bad taste’ or not. The photographer herself can be seen wearing a leopard print coat in the reflection of the caravan window.

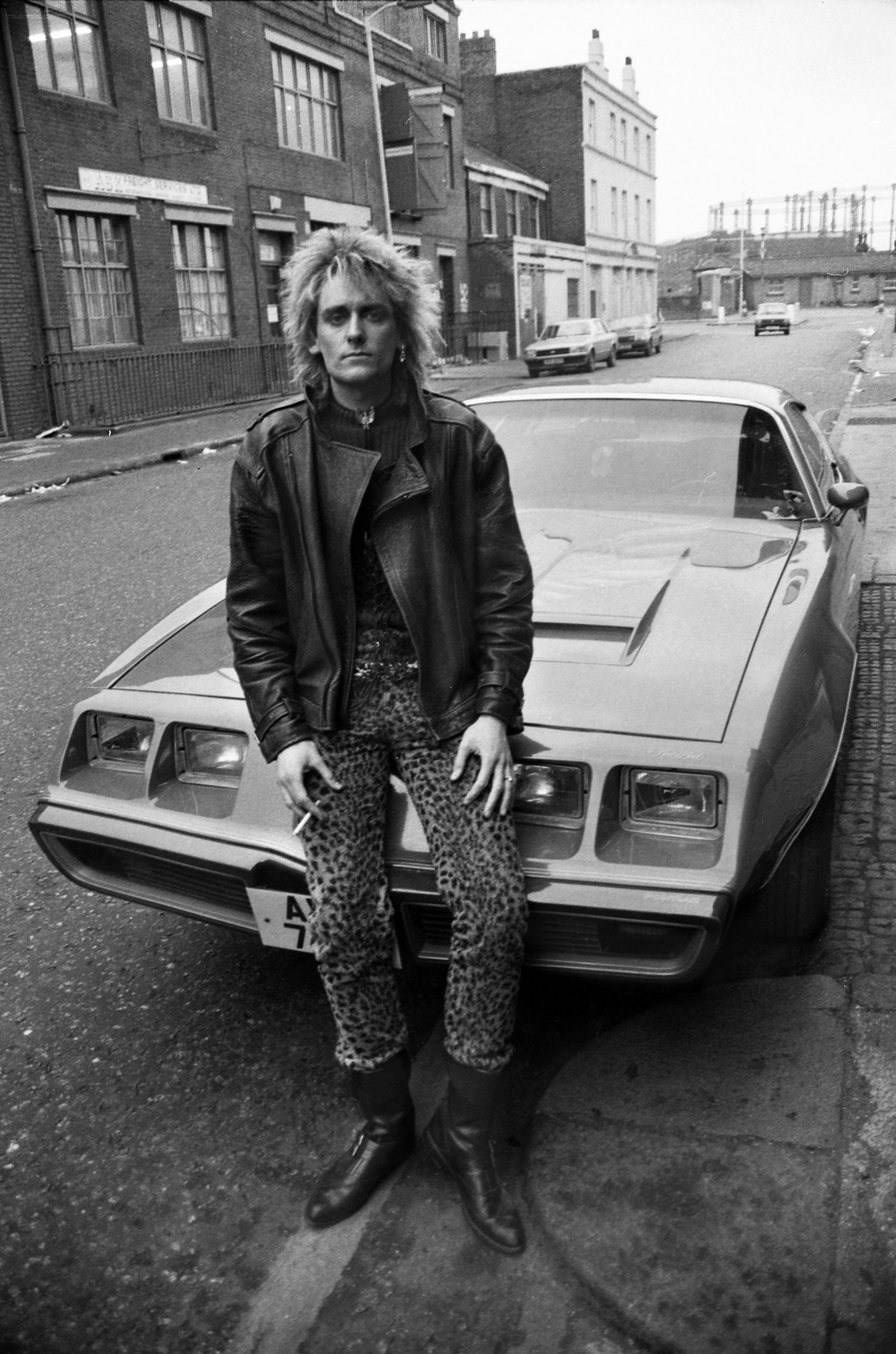

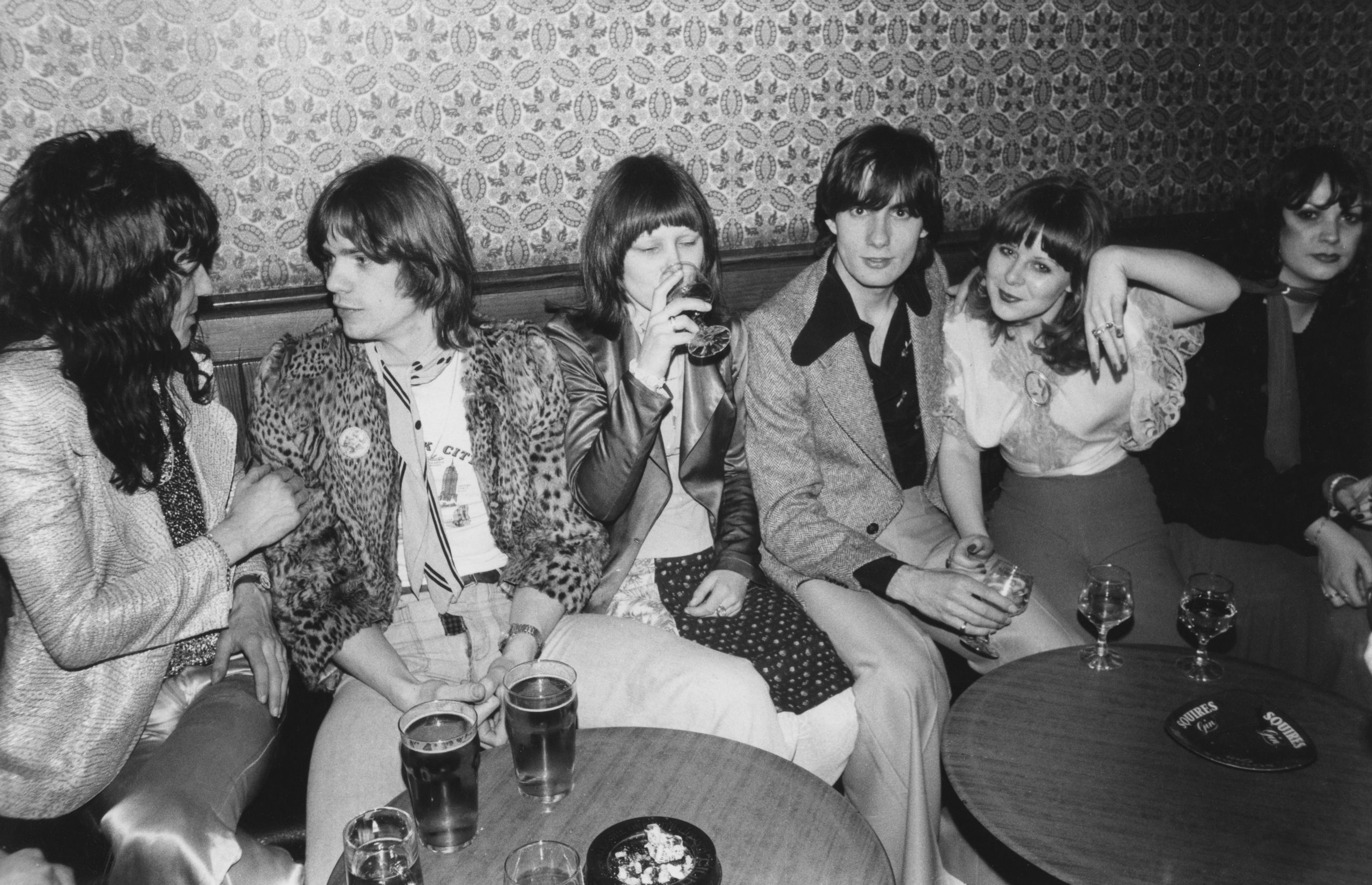

The class dynamics of leopard print, and fashion more widely, are not linear. Fashion is concerned with the production of different identities and one’s sense of self and it would be inaccurate to suggest that people of the working class merely sought to emulate fashion produced by the wealthier upper class and designer fashion houses. As one of the readiest means through which individuals make visual statements about themselves, fashion has always been a principal component of working-class youth subcultures. While Mods wore the print to project a rebellious respectability against the material conditions of their lives, throughout the 1970s and 1980s leopard print became a wardrobe staple for other youth sub-cultures that sought to voice their rejection of mainstream societal values. For Rockers, and Punks it became a protest against the establishment.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the gendered understandings of leopard print were confronted by rock and glam rock artists including David Bowie, Rod Stewart, and Freddie Mercury. Leopard print was a component of their camp aesthetic that sought to subvert traditional gendered understandings of the feminine and masculine. Its contemporary association with femininity and hyper-sexuality made it the perfect print for male rock musicians who sought to flamboyantly challenge societal conceptions of masculinity, much to the outrage of the more conservative public. Gavin Watson and Alexander Apperley’s images from this period show how young men engaging with rock subcultures too began wearing the print. Though everyday employment of leopard print did not often mirror the same extravagance of musician’s stage outfits, it demonstrates fashion’s ability to communicate membership to a youth culture and create a sense of belonging among people in that culture. Leopard print was not only used by male Rockers during this period but also by women who wore the print for its associations with ‘bad taste.’ Though rock was, and continues to be, dominated by male musicians, female rock stars such as Blondie’s Debbie Harry became fashion icons for young women. Effortlessly chic and sexy, her 1979 leopard print jumpsuit is now a part of fashion history, but in the 1970s it represented her use of the print at a time when it was considered the height of tackiness. Rockers were unafraid of subverting gendered fashion norms and introduced the potential of leopard print as a print of protest that would also be used by the developing punk movement.

While male rock stars used the print to flamboyantly subvert ideas of gender norms and sexuality, Punk employed it for all its negative associations with an outrageous anti-respectability. It was a working-class subculture contextualised by a period of deep economic crisis and the failure of the 1960s counter cultural movement to bring about its promise of revolution. The rise of Punk in the United Kingdom and other western societies represented rebellion against mainstream society in all its pretensions and excesses, accompanied by a soundtrack and visual imagery that broke the status quo and made visible a dissatisfied youth. Fashion played a significant role in the Punk identity, enabling an ‘us and them’ distinction and creating a sense of unity and belonging within the subculture. Punk was anarchic, nihilistic, and deliberately aggressive. Leather, rubber, vinyl, and ripped denim were materials of choice for Punks, accompanied by slogan tees with safety pins and Dr Martins. Paul Anderson’s ‘Female Punk’ demonstrates how leopard print was paired alongside leather jackets, fishnet rights and spiked hair in the cultivation of Punk’s visual image. His image ‘Male Punk’ also demonstrates how gendered conceptions of the print continued to be subverted in Punk culture. However, in contrast to the adoption of the feminine by male glam Rockers, leopard print underwent a masculine transformation in Punk.

Punk musicians such as Wendy O. Williams, lead singer of Plasmatics employed leopard print alongside on-stage theatrics including partial nudity, explosions, shotguns, and chainsaws to visualise her revolt against conformity to a conservative society and culture. One of the most well-known of Wendy O. William’s use of the print is a Vanity Fair jumpsuit worn backwards with duct tape covering her nipples, as seen in the image taken by Peter Anderson at a performance in San Francisco in 1980. The print was worn by Williams and other Punk women to signal their rebellion against a demand that they conform to a middle-class respectability and ‘good taste’ that often confined them to a subordinate position in society. Leopard print in Punk was not only for women, as men too donned the print to visually articulate their rebellion to conformist demands, however in contrast to the gender subversion of 1970s rock and glam-rock, Punk men’s use of the print remained heavily masculine.

Not only was leopard print used as a print of protest among Punks and Rockers as a visual representation of their rejection of conformity to a conservative mainstream society, it is also an important political aesthetic in Drag culture. At its core, Drag is a challenge to the socially constructed categories of identity including gender and sexuality. Clothing is the central aspect of drag performativity, contesting patriarchal and heteronormative understandings of masculine and feminine dress. Due to its associations with hyper-femininity and female sexuality, leopard print has been employed by Drag Queens specifically, as they seek to parody mainstream understandings of the feminine. This can be clearly seen in Tristan Fewings images from Horse Meat Disco’s construction of the New York drag scene. The images show one queen in a skin-tight leopard print jumpsuit, hugging her padded figure, and another in leopard print dress and fishnet tights. Leopard print’s place in the drag queen’s aesthetic arsenal of gender subversion is highlighted in Alaska Thunderfuck’s recent song ‘Leopard Print,’ from her album ‘Vagina.’ Throughout the song, Alaska repeats the refrain ‘everything must be leopard print’ and towards the end of the song declares ‘it’s the leopard print takeover.’ With leopard print, Drag Queens have transgressed understandings of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ taste and of the ‘trashy’ and respectable,’ turning the print into a political weapon to push back against middle class understandings of how a woman should look and behave. In the 1970s Divine became one of the most famous drag queens in the world due to her appearance in numerous John Waters films, including Pink Flamingos (1972) and Female Trouble (1974). Both on and off screen, Divine used leopard print to disrupt ideas of acceptable style, conventional beauty, and appropriate behaviour. In Pink Flamingos, Divine plays an exaggerated version of herself, a woman who has been deemed ‘the filthiest person alive,’ with the most famous scene in the film seeing the ‘trailer trash’ Divine eat dog faeces off the street. Much like punk, Divine employs leopard print for all its negative connotations, it is loud, outrageous, trashy, and camp. In Pink Flamingos, to be ‘filthy’ is recast as an aspirational pursuit of the upper classes as the villains of the film seek to prove themselves to be filthier than Divine.

However, while leopard print has been employed by queens such as Divine to challenge normative assumptions of gender and sexuality, it has also played a role in reinforcing gendered stereotypes. Drag queen performances often simultaneously deconstruct heteronormative gender ideals while reinforcing traditional societal images of women. C. Greaf has suggested that through their feminine performance, drag queens can justify the pre-existing social ideas of femininity, that it means to have a select type of stylized hair, make up, clothing and body language. In performing gender, queens have used leopard print to reaffirm the gendered assumptions about age, class, and sexual availability. In drag, leopard print is often used for its overtly sexual connotations. Much like normative assumptions about the women who wear leopard print, drag solidifies stereotypes of the young sexually available woman and the middle aged, desperate, and aggressive ‘cougar.’ The affirmation of hegemonic and oppressive stereotypes associated with gender identity, sexuality, class, race, and ethnicity within drag has come under increased scrutiny in recent years with the rise of drag in mainstream popular culture in the form of RuPaul’s Drag Race.

The 1990s saw a return of the print to ‘mainstream’ fashion culture with supermodels the likes of Kate Moss and Naomi Campbell wearing it from head to toe for fashion house Azzedine Alaia. The print appeared on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar, Vogue, Cosmopolitan and Dolly Magazine. The sight of leopard print back on the runway may seem to signal the end of its subversive potential, however the print’s resurgence on the catwalk occurred simultaneously alongside the rhetoric of Girl Power. Rather than representing an end to the print’s association with protest, it became emblematic of the re-emergence of feminism in the 1990s. Espoused most famously by the Spice Girls, Girl Power sought to appeal to young teens, and their use of leopard print imbued it with an understanding of women’s independence, self-confidence, and the notion of sisterhood.

The Spice Girls assertion that there was no right or wrong way to be a girl or a woman expanded the boundaries of femininity and rejected previous definitions placed on women’s bodies. Young women had the right to be sexy, trashy, sophisticated, independent, fierce, sporty, and girly and had the right to be all these things without any input from men or anyone else. Leopard print exploded in 1990s popular culture as women employed it to visually articulate their powerful independence, for example Shania Twain in her music video for ‘That Don’t Impress Me Much’ dons a full leopard print outfit and accessories as she makes her own way home from being stranded in the desert, rejecting men who attempt to help.

This 90s feminist message of women’s empowerment, freedom and individuality had limitations. Girl Power addressed young women and girls while older women remained excluded from leopard print’s new feminist leanings. There was also the commodification of the feminist message as a product to be bought and consumed in the form of music, film, and merchandise. While leopard print had been used by punks as a symbol of the rejection of a conservative capitalist society, 1990s feminism embraced capitalism. Moreover, while each of the Spice Girls donned leopard print at some point, it was most heavily associated with Mel B (Scary Spice), and therefore with a certain ‘type’ of woman. Mel B’s ‘Scary Spice’ persona has been described as ‘loud,’ ‘wild,’ ‘crazy,’ ‘confrontational,’ ‘aggressive’ and ‘intimidating.’ As the only mixed-race member of the band, the racial contours of the invented persona are interesting to consider. The words used to describe Scary Spice’s personality are indicative of the ‘angry Black woman’ stereotype, and therefore her trademark leopard print uniform was designed to provide a visual extension of this personality. However, Mel B also provided young Black and mixed-race girls and women in the 1990s a reflection of themselves in the biggest girl band in the world. Mel B/Scary Spice provided an example of an empowered Black woman, refusing to straighten her hair for the ‘Wannabe’ video and refusing to surrender to white beauty standards. Speaking in 2019 about returning to Scary Spice’s leopard print outfits, Mel B said it made her feel like she was ‘reclaiming who I was’.

Throughout the twentieth century leopard print accumulated meanings. Its inherent connection to identity ensured its continuous reformulation depending on who it was claimed by and those who rejected it. Gender, class, and age operated simultaneously to determine readings of leopard print from powerful, luxurious, practical, sensual, tacky, trashy, desperate, outrageous, and subversive.

Today, leopard print can be found everywhere on every body. Michelle Sank’s image of two young teenage girls in the 2000s demonstrates the apolitical nature of the print when worn by younger girls potentially unaware of its long and contested history. It is found on the runway, on the high street, on men and women, on the young and the old. Leopard print has become such an enduring staple in the fashion industry that it is now considered a ‘neutral.’ Yet the print continues to be an important part of youth culture and tool of personal expression. It continues to accumulate meanings and continues to spark conversation. Whatever your opinion, leopard print is here to stay.

Lauren Eglen is a postgraduate researcher at the University of Nottingham in the department of American Studies. As part of her broader research interests in feminist activism in twentieth century U.S. social movements, her doctoral thesis explores women’s editorship of the Black radical magazine, Freedomways, 1961-1985.

Commissioned as part of a Research Internship Programme in collaboration with the Centre for the History of People Place & Community at the Institute of Historical Research. Supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund as part of Setting the Record Straight