With super sharp looks and a whole load of attitude, Rude Bwoys came swaggering into the British youth scene. With their roots in Jamaica, UK youth movements were quickly inspired, and before long people dancing to Ska and Reggae. This essay will look at how this movement took Britain by storm and inspired generations of young people.

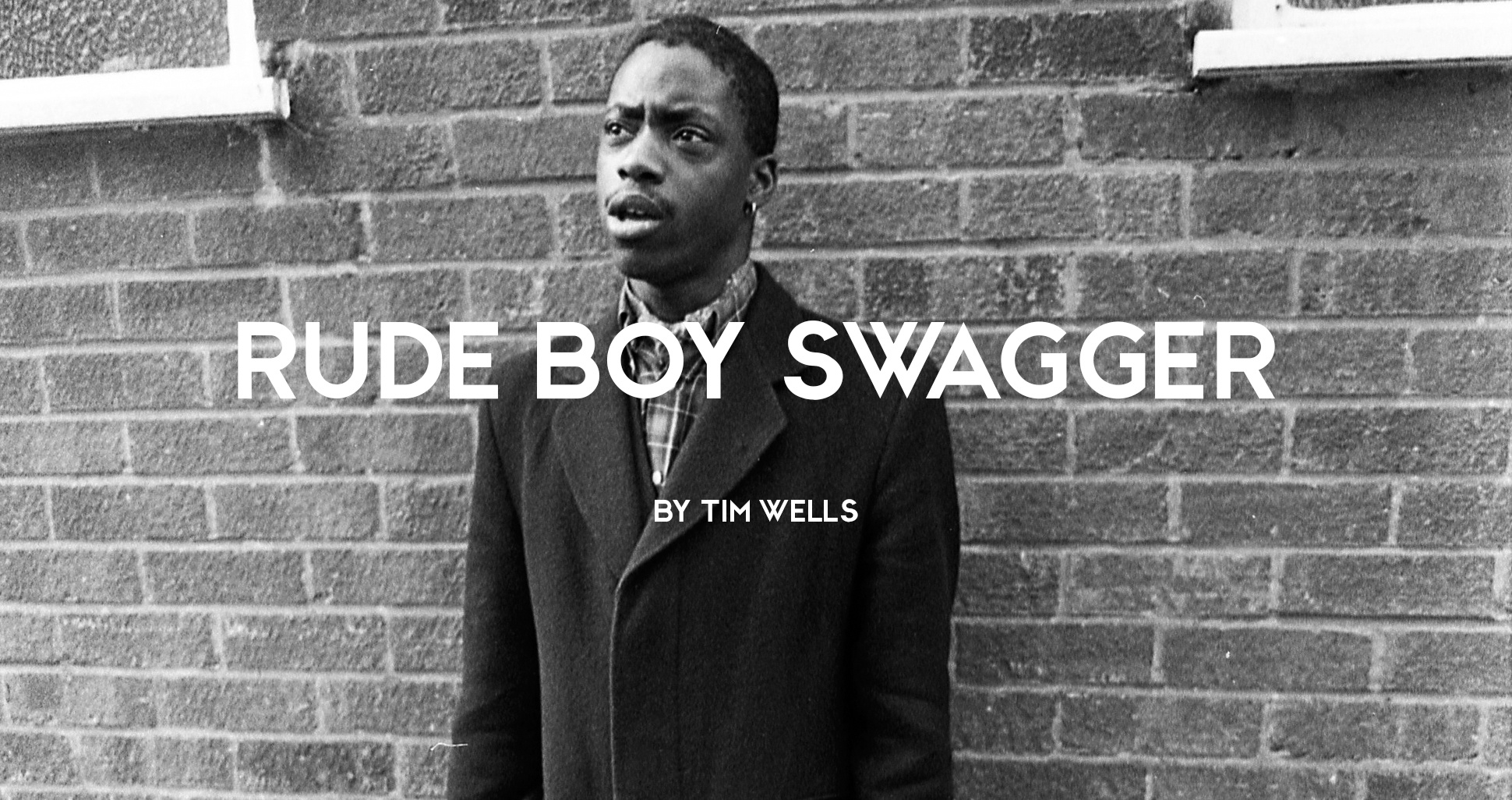

Text by Tim Wells, Cover Photo by Gavin Watson.

The tight knit group of lads round the stereo wearing knit shirts and blaring reggae, the ones whose eyes fiercely warn ‘don’t even try fe reach fe no pop records’ are givin’ it in style and attitude: rude bwoys.

From the 60s to mid 80s, even with changing sartorial and musical stylings, rude bwoys stayed a crucial part of inner city Britain’s yoof culture. Originally springing from gangs that followed Jamaica’s partisan sound system they were soon cutting a dash in Britain’s dancehalls to ska and jazz, Sam Selvon’s ‘The Lonely Londoners’ and Colin MacInnes’ novels documented their swagger through London. A knife edge crease and a pork pie hat tilted with attitude in response to poor housing, poverty, and out and out racism.

Though made in the 70s the Jamaican film ‘The Harder They Come’ tells the tale of a Kingston rude bwoy, played wonderfully by Jimmy Cliff. The story is based on Ivanhoe ‘Rhyging’ Martin, a Jamaican folk hero to the have nots, and as it always is with folk heroes, a folk devil to the haves. Rhyging also lived on in a Prince Buster song, a 1966 Miss Lou poem. He even gets name checked in the Clash’s ‘Guns of Brixton’.

Ska and rocksteady records are peppered with references to rude boys. Prince Buster’s ‘Judge Dread’ was sentencing them to jail and a ridiculous amount of lashes, The Rulers harmonised ‘Don’t Be A Rude Boy’, and the Wailers sang ‘Hooligan’ and ‘Good Good Rudie’. The rude bwoy was always crashing the dance and causing trouble, and they looked good doing it.

British mods quickly picked up on Jamaican ska music and natty fashions of their West Indian neighbours. In 1968 as ska had gone through rocksteady the skinheads became synonymous with reggae. Their clean cut antithesis to hippy came from the American Ivy League look sported by the astronauts all over the news as well as Jamaicans at the dancehalls.

"The tight knit group of lads round the stereo wearing knit shirts and blaring reggae, the ones whose eyes fiercely warn ‘don’t even try fe reach fe no pop records’ are givin’ it in style and attitude: rude bwoys."

In the early 70s roots reggae became big and the rasta became a recognised look for reggae. Rasta was spiritual, peaceful, and loving whilst the rude bwoys wanted success, money, good times and they wanted them now. That they weren’t available to everyone in a divided and tense Britain didn’t lessen that hunger any. As in Jamaica, back a’ yard, the rude bwoys followed sounds systems in the same way that lads followed football teams, and often in Britain with a bit of overlap. The same territoriality, rivalry, and passion followed the sounds as well as the outbursts of trouble that were so common a feature of 70s inner city Britain. The 1980 film Babylon is an excellent portrayal of sound system culture, and a picture of Britain at the time. The music, look, and experiences expressed in the film are spot on.

Punk morphed with reggae in 2 Tone, and its fans took the name Rude Boys. The figure sporting a decent suit and pork pie hat on the 2 Tone record label was known as Walt Jabsco and the drawing of him was based on a photo of the Wailers’ Peter Tosh, these 2 Tone rude boys skanked in a mix of mod and skinhead fashions to up-tempo songs that often had downbeat subject matter. This swept up many pop fans but, as ever, reggae was doing its own thing.

In the late 70s dancehall became the dominant style of reggae. This moved away from the spiritual concerns of rasta and the rude bwoy was ranking. Barrington Levy, General Echo, Lone Ranger and more were on the record deck. British label Greensleeves, deliberately making use of the name of that most English of songs for their output of hard Jamaican music, put out 12” after 12” of glorious reggae music. The 12” sleeve even had a great ‘carnival of reggae’ drawing on the front that showed the evolution of reggae music on it, even punks and policemen were depicted. The 1983 sociology book Inside The Inner City by Paul Harrison has a detailed description of Dalston rude bwoys: ‘The tea-cosy hat and the bomber jacket are signs of plodding poverty: the style that the fashion setters have adopted is not Rasta, but straight from the pages of The Tattler, gold-buttoned, double-breasted blazers, silk shirts, camel-hair coats, Burberries. There are distinctive exotic elements too: broad-brimmed leather hats, tall peaked caps in pure-wool tweed, gold bracelets and pendants, and a whole status hierarchy of shoes in which sneakers are the bottom rung, leather is looked down on, and reptile skin is the rage: lizard, crocodile and ostrich-skin shoes costing up to £250 for a handmade pair.’ Barry Brown’s 1980 album Cool Pon Your Corner sees the singer sporting the look and the title track is one serious bit of dancehall that encapsulates rude bwoy.

Tim Wells is a poet and a writer who still buys discomixes. He is the editor of the poetry magazine Rising and runs the blog Stand Up and Spit.

This essay was curated by The Subcultures Network, which was formed in 2011 to facilitate research on youth cultures and social change, and commissioned as part of the National Lottery Heritage Funded project to build the online Museum of Youth Culture. Being developed by YOUTH CLUB, the Museum of Youth Culture is a new destination dedicated to celebrating 100 years of youth culture history through photographs, ephemera and stories.

The National Lottery Heritage Fund invests money to help people across the UK explore, enjoy and protect the heritage they care about - from the archaeology under our feet to the historic parks and buildings we love, from precious memories and collections to rare wildlife.

Tune In

Al Capone, Prince Buster, 1967

007, Desmond Dekker, 1967

The Upsetters, Lee Perry, 1969

Rude Boys, Bob Marley and The Wailers, 1965

Tougher Than Tough, Derrick Morgan, 1966

Turn On

Babylon, Franco Rosso, 1980

The Harder They Come, Perry Henzell, 1972